Syllabus

Welcome to Web Development and Design by Oval! We're happy to have you here. Over the course of this class, you will learn everything you need in order to build and publish your own fully functional website online.

In this course reader, you will find notes and tutorials for each lecture. While the entire course reader is available to you beforehand, we suggest that you read each chapter only after you have attended the corresponding lecture and have completed all previous homework (though feel free to take a look at what's to come!).

Schedule

The objective of this course is to equip you with the knowledge required to build your own personal website—be it a page about yourself, your favorite movie, your pet, or whatever else that you envision1. To do so, the course is split into 4 different units, with individual subchapters. Each subchapter has a supporting 2-hour lecture, notes, and homework. Some chapters refer to separate readings to support the knowledge that you obtain in lectures. During Chapter 1.2, you will set up a repository (directory) for your upcoming website, and all of the later assignments will help you improve it. Below is the table of contents—it covers everything from what is a browser to how to deploy your final website online.

UNIT 1 - Technical Foundations

Chapter 1.1: Browsers, Servers, Command Line Tools, IDEs.

How does a browser work? How does it retrieve information and how does it display it? This chapter focuses on the conceptual overview of computer networking and it will introduce you to the tools that every web developer needs to be comfortable with in order to build efficient websites rapidly.

Chapter 1.2: Introduction to Git. Introduction to HTML.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use Git, a version control system used by millions of developers. You will also learn about HTML—a markup language that defines the structure of every website that you ever visited. After that, you will set up a repository for your own starter website on Github.

Chapter 1.3: Introduction to CSS and Advanced HTML Tags.

This chapter covers advanced HTML elements such as buttons, images, as well as semantic tags to help you organize your code for readibility. It will also explain what is CSS and will teach you how to style your HTML elements (i.e., how to add colors, margins, background images, etc).

UNIT 2 - Design

Chapter 2.1: Introduction to User Interface Design.

We will take a break from coding and explore what makes a website visually appealing and easy to use. What is a design personality? How to use typography and colors to define your website personality? What is a design system? After completing this chapter, you will be ready to answer questions like these, will know about fundamental UI/UX design patterns, and will start sketching your own website.

Chapter 2.2: Advanced User Interface Design.

How to space elements of the interface? How to create color palettes? What are advanced techniques for designing text? After completing this chapter, you will equipped with the most essential tools for designing your website, will do advanced sketches for your own website, and will be prepared to learn about designing software in the upcoming chapter.

Chapter 2.3: Design Tools.

In order to be able to quickly and efficiently design beautiful websites, it is important to know how to use prototyping software. A very popular (and free) choice among developers is Figma—an online platform used by millions of designers. In this chapter you will learn how to use it and will be ready to start creating the final design for your website.

UNIT 3 - Introduction to Programming

Chapter 3.1: Programming in JavaScript.

So far you have set up the structure of your website, its elements, designed its appearance, and even know how to style them in CSS. But how do you animate your website to be dynamic and feature-rich? Here is where programming comes in. In particular, all browsers use JavaScript to add programmed components into your website. Before progressing to implementing the design that you have developed in the previous unit, we will learn how to make a website interactive. In this chapter, you will learn fundamental computer science concepts like variables, conditional statements, and loops, and will learn how to use them in JavaScript.

Chapter 3.2: Functions and Event Handlers.

How do you set up your website's elements such that the user can interact with them and can change the state of your website? The solution is to use event listeners and handlers. In this chapter, you will learn about JavaScript functions and how to use them to make elements of your website interactive.

UNIT 4 - Responsive & Rapid UI Design

Chapter 4.1: Element Alignment and Tailwind CSS.

Positioning elements on a website can be tricky. After this chapter, however, you will master this skill—we will show you what is a CSS Flexbox and Grid Layout and how to make prototyping them a lot faster using a utility-first CSS framework Tailwind CSS.

Chapter 4.2: Layout, Positioning, and Responsive Design.

How do you position your elements on the screen and organize them into containers and grids? How do you make your website look good on all devices, regardless of their screen dimensions? In this chapter, we will learn what Tailwind CSS capabilities you may use to organize your content and optimize it for different screen dimensions.

Final classes

Beyond HTML, CSS, and JS. Office Hours.

The previous ten chapters have covered a substantial amount of information — in fact, we've designed them to cover the most important insights and skills we've gained ourselves over multiple years of web development. By now, your website is almost ready, though we realize that you may still have lingering questions. Use this time to ask us anything! Besides that, we will cover some of your possible next steps beyond the course during the lecture. For homework, you will finalize your website and deploy it online.

Project Presentation.

Congrats! You've worked very hard and we hope you are proud of what you have built. Share your website with us!

Course Policies

This course is fast-paced: over the duration of the course, you will learn fundamentals of computer science, networking, and front-end web development. In order to make sure that everyone is keeping up with the workload and is getting a solid grasp of the material, each lecture will be followed by homework that is due the upcoming lecture. For example, Lecture 1 will have Homework 1 that will be due Lecture 2.

1 Within reasonable complexity constraints, of course — we can't teach you how to build a new startup in one month, but you are definitely going to be proud of what you build!

Chapter 1.1 - Browsers, servers, command line tools, code editors.

Browsers, servers, command line tools, code editors.

In order to be able to build and deploy fascinating websites like you are about to create, you need to know the basic concepts first. In this chapter, you will get familiar with how browsers work and how they send requests to servers. Once you know that, we will transition to talking about tools that you will need to build your awesome website.

Chapter 1.1.1 - What is the Internet?

Before we delve into complicated questions, we need to answer a more fundamental one — what is the Internet. Generally speaking, it's a network of connected computers just like yours. They're connected in various ways: some are connected to the Internet with optic fiber (that travels at the speed of light), some with cellular networks, some with Wi-Fi, etc. What unites them is the languages they speak: protocols for exchanging information. The architecture of the Internet is very complicated and we will not go in-depth on these topics (save that for an advanced undergraduate course). However, we will provide a friendly overview of the most important components that we believe are crucial to know before you can embark on the journey of building your own website.

IP addresses

In most cases, each computer in the Internet has its own address. If you're on a shared Wi-Fi, than your computer would share the same IP address as other computers connected to the router, although it would still be a unique address. Sometimes they change: that's called a dynamic IP address. In most cases, though, the IP addresses are static. What's the difference? There's no fundamental difference, other than the fact that they change, and the reason why that happens is because your IP address is assigned to you by your Internet provider, and sometimes they recycle them for internal purposes.

Client vs. server

There are two main participants in the exchange of information via the Internet: the client and the server. The client is the computer that sends a request for some information to the server, and the server is the computer in charge of returning some requested information back to the client. For example, when you go to https://apple.com, you are the client and you are sending a request to some of the Apple's servers.

There are also two types of IP addresses currently available: IPv4 and IPv6. For the purposes of this course, we will only deal with IPv4 addresses. IPv4 address is represented by four numbers less or equal to 255 split by a dot (i.e. 192.168.0.1). Why 255? That is the maximum value that a byte can hold.

Server ports

Think of servers as office buildings. To reach a particular office, you would first need to know the address of its office building (IP address). Then, you'd need to know the office number. The analogy of an office number for servers is a port number: a digit ranging from 0 to 65536. Why 65536? That is the maximum value that two bytes can hold (though don't worry about this, and you certainly don't need to memorize that number). There are some conventions for port numbers; here are just a few:

- 21 is for FTP servers (File Transfer Protocol)

- 80 is for HTTP servers (Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol; explained below)

- 443 is for HTTPS servers (Secure HTTPS; explained below)

80 and 443 are so common that you don't actually need to type them in your browser — simply use the IP address. For other ports, you would need to write the IP addresses followed by a colon and by the port number (i.e., 192.168.0.1:21). The website you will build will be available at ports 80 and 443 (unless you don't want others to be able to find them).

HTTP/HTTPS

HTTP is the protocol used by practically every website you ever visited. It is a standard protocol that your computer uses to form a request to the server and that the server uses to compile necessary information and send it back to you. For example, if you visit https://apple.com, your browser would actually create something like the HTTP request below and send it to Apple (this will differ from computer to computer). Note that it contains my operating system, my language, and other metadata that will allow Apple to customize their response to me.

GET / HTTP/2

Host: www.apple.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:88.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/88.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

DNT: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: ...

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Sec-GPC: 1

In response, Apple would send back the HTML file for https://apple.com. What is HTML? You will learn that in Chapter 2 :)

You don't need to know what each of the lines in the above request means, except the first one — that's the kind of HTTP request that you are sending. There are quite a few possible requests. Here are the most common ones:

GET: used to retrieve informationPOST: used to post/update information (usually sent with some payload, i.e., the data that you want to update)DELETE: used to delete some informationOPTIONS: used to retrieve available HTTP methods (for example, not all servers supportPOSTor evenGET)

For the purposes of this course you will likely only use GET. If you were to build a complicated server with a database, you would need to support more methods. When you visit a website, your browser always sends a GET request. In fact, you can't conveniently send anything else unless you send it in code (you will learn JavaScript in Chapter 6).

HTTPS is just a secure version of HTTP. Essentially, before sending this HTTP request above, your browser would encrypt it and the server would decrypt it — that way anyone in between (for example, your Internet provider) would not know what you are sending and receiving. How exactly that works is beyond the scope of this class, but trust us when we say some brilliant people created it and it's definitely secure.

DNS

The final important concept for understanding websites is DNS — the Domain Name System. As we mentioned above, each computer connected to the Internet has an IP address, but people are not good at memorizing four arbitrary-looking three-digit numbers, and so the founders of the Internet created DNS — a way to map easily memorizable domain names like apple.com to less memorizable addresses like 17.253.144.10 (which is the real address behind that domain, at least for my computer). There are many ways to configure DNS when you get your own domain, but here are the two most relevant records:

- A: maps an IP address to a domain name

- CNAME: stores a canonical name for your domain (in other words, an alias)

Chapter 1.1.2 - What is a browser?

A browser is a kind of software that allows you to very conveniently navigate the web. Here's how it does it:

- When you go to some website, your browser contacts the DNS server to learn what is the real IP address for its domain name (recall our Apple example in the DNS section).

- Once your browser knows the IP address, it sends a

GETrequest to that IP address describing what it wants to retrieve. For example, when you visited this page, your browser sent aGETrequest to the IP address of the server that's hosting this page and asked to retrieve the HTML filechapter-1.2.html. - Once the browser receives the requested HTML file back, it starts to analyze it and build a DOM-tree (more on that in Chapter 2). For now, think of that as an internal structure of the website. If a file that you requested is not HTML, then other methods of displaying are used (for example, a PDF file would be displayed with a PDF reader). If your browser can't display a file, it prompts to download it to your hard drive. Every website you visit uses HTML.

- Once the browser has created the DOM-tree of the HTML page, it starts to render it. Meanwhile, if the page contains images, your browser sends additional

GETrequests to retrieve those files so that it can display them.

All of that happens within seconds, if not less!

One important thing that you should know is that, by default, if you don't specify a file and only specify the directory that you want to retrieve when going to a website, your browser will send a request for index.html. For example, when you visit https://www.apple.com/mac/, you browser actually sends a request for https://www.apple.com/mac/index.html, retrieves index.html, and renders it. Click both links to confirm that they lead to the same destination!

By now you may have noticed that the website addresses after the domain name look like addresses on your computer's filesystem. It's because they are! Essentially, a server is hosting a directory and you can access its files remotely. (Some website architectures are more complicated and actually generate files when you request them, but you don't need to worry about that.)

Exercise

Press Cmd+Shift+C (or F12) to go to Firefox's console, click the "Network" tab, then visit any website. Look at how many HTTP requests are needed just to display one website! Note also that the first request is a request for an .html file.

Chapter 1.1.3 - Command line tools

Back in the days, computers didn't have convenient user interfaces, and everything was done using the command line. Despite the advent of operating systems with accessible user interfaces, the command line is still a useful part of every system. In this section, you will learn how to use it.

Families of operating systems

There are two main families of operating systems systems: Unix and DOS. DOS was developed by Microsoft and it is used in Windows operating systems. Unix is derived from AT&T Unix, developed in 1970, and it is used in both Linux and Mac OS. The command line tools and syntax differs between these two systems, but we will use Unix throughout this course.

Current working directory

When you use a command line, you are located within a directory from which you can access other files and directories. For example, if you open the Terminal (command line) in Mac OS, by default the current working directory will be set as your home directory located in /Users/$USER (where $USER is your username). From there, you can access all files and directories within that folder with their respective names.

Executables

The command line allows to run executables (or, simply, programs). In order to do so, simply type the name of the executable you wish to run and pass the required arguments (parameters), if needed. For example, in Unix, cd is an executable that allow to change directories. If you are in your home folder on Mac OS, you can navigate to "Documents" by typing cd Documents. Here are other useful executables:

ls: lists the contents of the current working directory. If a parameter is passed, it lists the contents of that directory.pwd: prints the path to the current working directory.rm: removes the given file (for example,rm a.txt).mkdir: creates a new directory (for example,mkdir new-directory).

If you want to pass a parameter with spaces, wrap it inside quotation marks. For example, if you want to create a directory called "New Directory", type mkdir "New Directory".

There are many other executable that come with Linux/Mac OS and executables that you can install yourself, but these are the most common ones that you need to remember.

Flags

Executables can also accept flags to change their behavior. Flags are similar to arguments but are prefixed with either - or --. For example, ls accepts an -a flag which would force ls to print hidden files within the directory (hidden files are simply files that are not visible by default and whose names start with .). rm accepts -r flag which forces rm to traverse the files within the given directory (and their files) and delete them too. For example, if you were to run rm -r /Users/$USER/Desktop, you would erase all desktop contents! (You should probably not try it.)

Absolute vs relative paths

An absolute path to a file or a directory is a path that includes all folders starting from the root directory /. For example, the absolute path to Desktop on Mac OS is /Users/$USER/Desktop.

A relative path to a file or a directory is a path to it from your current working directory. For example, if your current working directory is /Users/$USER, the relative path to Desktop is Desktop.

Each Unix directory also contains a link to itself and to its parent directory:

- The alias for the parent directory is

... A parent directory is a directory that contains another directory, which is its child. For example,/Usersis a parent directory for$USER, which is its child directory. If your current working directory is/Users/$USERand you runcd .., your current working directory will change to/Users. - The alias for the current directory is

.. If your current working directory is/Users/$USERand you runcd ., your current working directory will remain the same.

Finally, there is another useful alias for the home directory: ~.

PATH

Usually, you need to give the path to an executable that you wish to run. For example, if you create an executable called my-executable and place it within your current working directory, you would need to run ./my-executable (note that you need to include the alias to the current working directory). However, it would be tedious to know where each executable is located within your filesystem, and so Unix provides a global variable called PATH that contains folders with executables that need to be accessed globally. When you type ls, your operating system actually goes through each folder in PATH and checks if it contains that executable. It then finds the directory with the absolute path of /bin and runs ls within it. If you want to know where a global executable is located, run where followed by the executable's name. For example, where ls outputs /bin/ls.

Chapter 1.1.4 - Working with code editors

Practically speaking, you can write websites in any text editor. However, there are specialized code editors that help you write clean, formatted, error-free code—sometimes they even write code for you! There are many choices out there, from IDEs (Integrated Development Environments) like WebStorm to universal code editors like Sublime Text, Atom, and Visual Studio Code. Since we want you to pick up a tool that you can use no matter what project you are working on, we will stick to universal code editors. Specifically, we are going to use Visual Studio Code, as its extensions library has thousands of ways to improve and speed up development. We are not going to do a better job describing what Visual Studio Code is than Microsoft themselves, so read more about it on their official website.

Homework

The homework for this chapter will make you install, configure, and play around with Visual Studio Code. This will be our main development tool throughout the course, so make sure to carefully follow the instructions below.

Part 1: Installation

Navigate to https://code.visualstudio.com/, download the appropriate version for your platform (the homepage should automatically detect your system), and install it.

Part 2: Extensions

Since Visual Studio Code is just a code editor, it allows developers to work in any programming language. However, it also allows them to build extensions for their favorite languages which they can then share with the world. We will use a few such extensions to improve our experience of building websites. Since we haven't covered any programming so far, you don't have to know what these extensions do yet — just make sure to install all of them. To do so, take a look at this guide: https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/editor/extension-marketplace. Once you have learned how to install and uninstall extensions, search and install the following ones:

- HTML Snippets (by Mohamed Abusaid):

abusaidm.html-snippets. - HTML Preview (by Thomas Haakon Townsend):

tht13.html-preview-vscode. - HTML CSS Support (by ecmel):

ecmel.vscode-html-css. - Tailwind CSS IntelliSense (by Brad Cornes):

bradlc.vscode-tailwindcss. - Headwind (by Ryan Heybourn):

heybourn.headwind.

Feel free to install other extensions if you find something that you like!

Part 3: Configuration

Click Cmd+Shift+P or Ctrl+Shift+P and go to Preferences: Open Settings (UI) (you may type it). In the Commonly Used tab, set "Tab Size" to 2. Now go to Text Editor → Formatting and enable "Format on Save".

Part 4: Play Around

Now that you have set up Visual Studio Code, try to experiment! Create a new project and create a index.html file. Now, paste the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Experiment</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello from Oval!</p>

</body>

</html>

If you've set everything up properly, when you save the file (Cmd+S or Ctrl+S), it will be formatted and turn into

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Experiment</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello from Oval!</p>

</body>

</html>

Now, in the Explorer tab on the left of Visual Studio Code (the top one), right-click on index.html and click "Reveal in Finder" (or "Reveal in File Explorer" on Windows). This will open the directory containing your project outside of VSCode. Run index.html and you will see a browser tab containing a website that just says "Hello from Oval!". Congratulations, you have just written your first website! Don't worry about what the code does — we will cover it in the following lectures.

Chapter 1.2 - Introduction to Git. Introduction to HTML.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use Git—a free and open source distributed version control system designed to work on small or large projects in collaboration with other programmers. It can be used locally on your computer to keep track of changes you make to your project, or online with Github to collaborate with people across multiple networks. After learning about Git, you will learn the basics of HTML and set up your own project on Github.

GitHub is the industry standard for showcasing your programming portfolio. Technology companies and universities like to see what you have been working on and GitHub provides an easy way to showcase that.

By the end of this course, you will be hosting a fully-customized portfolio site, built from scratch, on GitHub Pages—a static website hosting service that takes HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files straight from a repository on GitHub, optionally runs the files through a build process, and publishes a website.

Install Git (Windows only)

Git is installed on Linux and macOS computers by default. However, Windows does not include it. If you are using a Windows machine, follow the instructions below to install Git onto your computer.

- Open the Git website.

- Click the Download link to download Git. The download should automatically start.

- Once downloaded, start the installation from the browser or the download folder.

- In the Select Components window, leave all default options checked and check any other additional components you want installed.

- Next, in the Choosing the default editor, select VS Code.

- Next, in the Adjusting your PATH environment, we recommend keeping the default Use Git from the command line and also from 3rd-party software as shown below. This option allows you to use Git from either Git Bash or the Windows Command Prompt.

- Next, we recommend leaving the default selected as Use OpenSSH.

- Next, in Choosing HTTPS transport backend, leave the default Use the OpenSSL library selected.

- In the Configuring the line ending conversions, select Checkout Windows-style, commit Unix-style line endings unless you need other line endings for your work.

- In the Configuring the terminal emulator to use with Git Bash window, select Use MinTTY (the default terminal of MSYS2).

- Click the Install button

If you are on Windows, use Git Bash (a Unix-based shell) throughout the course. In our experience, it is a lot more beneficial to learn Unix shell than Windows, and so we will not be including Windows-based examples.

What is HTML?

HTML stands for Hyper Text Markup Language. This is the language that is used across all of the websites on the internet to display information. HTML files are just plain text files (with .html extension) that consist of a series of elements which tell the browser how to display the content you type. Since HTML is just a markup language, there are no special programs that you need other than VSCode!

Chapter 1.2.1 - Understanding Version Control, Repositories

Version Control

Version control is a system that records changes to a file or set of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later. Git essentially takes snapshots of your code—it records the entire state of your project at different moments in time so that you may revert to those snapshots if needed.

Git Repository

A repository is simply a directory that somebody has initialized with Git.

In order to initialize Git inside a directory, type the following command into your command line (remember to use Git Bash if you are on Windows):

git init

This command creates a .git subfolder in your directory where Git keeps track of your changes. By default, files and directories that starts with a period . are not visible in Finder or File Explorer. To see hidden files, enable this setting in your operating system or run ls -a.

If you ever clone (copy) someone else's repository, it should already contain .git/ inside and so you don't have to run git init.

In short, a repository (or just "repo") is a set of files and subfolders that Git tracks for you.

Chapter 1.2.2 - Configuring Git

To be able to use GitHub and Git on your machine, you have to create an account on GitHub.

Once you have your account set up, open up your Terminal application and tell Git your name and email:

git config --global user.name "Your Full Name"

git config --global user.email your_email@email.com

For example, Jon Doe, whose email is JonDoe@outlook.com would type:

git config --global user.name "Jon Doe" git config --global user.email "JonDoe@outlook.com"

Chapter 1.2.3 - Creating a Git Project

Let's create a new directory for our sample Git project.

In Mac or Linux, open Terminal and type the following commands (you don't have to include anything after #—they are just comments and don't affect anything):

cd # takes you to home directory

mkdir test1 # creates subfolder called 'test1'

cd test1 # takes you to 'test1' subfolder

Now, put the directory under Git revision control:

git init

You have successfully created your first Git repo!

Creating a file and making changes

Now, let's add a file, make some changes, and commit them to Git.

Type the following command into your Terminal to create a text file that contains 'This is some text' inside:

echo "This is some text" > myfile.txt

Let's see what git thinks about what we're doing:

git status

The git status command reports that myfile.txt is 'Untracked'. Let's allow git to track our file by adding it to the staging area.

git add myfile.txt

Run git status again. It now reports that my file.txt is "a new file to be committed." Let's commit it and type a useful comment:

git commit -m "Added myfile.txt program."

We have successfully put our first coding project under git revision control!

To recap use

git statusto learn about the status of your project (that is, which files were created/modified/deleted)git add {filename}in order to track a file (you have to do this every time you modify it). If you don't want to list each modified file manually, simply typegit add .(the period is a wildcard for all files).git commit -m "{message}"in order to create a new "checkpoint" for your project which will include the entire current state of the repository.

Pushing Our Sample Project to GitHub

When programmers talk about "pushing" projects to GitHub, they essentially mean that they are synchronizing their changes with a repository hosted in the cloud where other people can see the code they have written. We will push our sample project to GitHub:

-

Create a new repository on GitHub. To avoid errors, do not initialize the new repository with README, license, or

gitignorefiles. You can add these files after your project has been pushed to GitHub. -

At the top of your GitHub repository's Quick Setup page, click to copy the remote repository URL.

-

In Terminal or Command Prompt, add the URL for the remote repository where your local repository will be pushed.

$ git remote add origin <REMOTE_URL>

# Sets the new remote

$ git remote -v

# Verifies the new remote URL

- Push the changes in your local repository to GitHub.

$ git push -u origin main

# Pushes the changes in your local repository up to the remote repository you specified as the origin

From here on, you will need to type only

git pushwhenever you want to synchronize your Github repository with your local repository.

You have now succesfully pushed your project to Github!

Chapter 1.2.4 - HTML Syntax

An HTML document is a text file that holds the layout of a website. To do so, it has a set of elements that it can use (buttons, generic containers, text containers, etc). Each element has a start tag, content, and a closing tag. The start tag starts with < and ends with >. The end tag starts with < and ends with />. Everything that's between the start and the end tag is the content of the element. For example, here is how a button would look like:

<button>Press me!</button>

Some elements are so-called self-closing tags. They don't have a closing tag, but their starting tag ends with />. There are not many of them, but, for example, <img> is a self-closing tag, and an image would like:

<img src="img/ostrich.png" alt="Ostrich Picture">

As you may have noted in the example above, elements may also have attributes—meta parameters. The most popular attributes are id, used to identify unique elements, and class, features that are shared among many elements. Don't worry about class yet—we will get back to it in the CSS section. In the example above, we used src and alt, which are unique to <img />: src contains a link to the image file, and alt contains a description of the image for accessibility purposes.

Elements provide extra information about the data in the document. They can stand on their own, for example, to mark the place where a picture should appear in the page, or they can contain text and other elements, for example when they mark the start and end of a paragraph.

Every HTML document has the following structure:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title></title>

</head>

<body></body>

</html>

The rest is up to you to fill in! For example, here is a sample webpage source code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>A quote</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A quote</h1>

<blockquote>

<p>The connection between the language in which we think/program and the

problems and solutions we can imagine is very close. For this reason

restricting language features with the intent of eliminating programmer

errors is at best dangerous.</p>

<p>-- Bjarne Stroustrup</p>

</blockquote>

<p>Mr. Stroustrup is the inventor of the C++ programming language, but

quite an insightful person nevertheless.</p>

<p>Also, here is a picture of an ostrich:</p>

<p><img src="img/ostrich.png" alt="ostrich picture"></p>

</body>

</html>

You can see what this website looks like by clicking here.

Elements that contain text or other pages are opened with <tagname> and closed with </tagname>. The html element always contains two children: head and body. The first holds information on the document and the second contains the document itself.

Here is a small list of tags to get you started:

| tag | function |

|---|---|

h1 | Stands for "heading 1". When characters are wrapped in this tag, they become a heading. Other variations of the tag include h2, h3, ..., h6 (the higher the number, the smaller the header). |

p | Stands for "paragraph". When characters are wrapped inside it, they become a new paragraph. |

img | Stands for "image". This tag does not contain displayable characters inside of it: it contains attributes such as src="img/ostrich.png" and alt="ostrich picture". It is also a self-closing tag. |

div | Stands for "content division". This tag is a generic container for other tags and does not have any impact without applied CSS styles. |

To learn more about HTML and see a comprehensive list of available HTML tags, visit the HTML Documentation from Mozilla Foundation.

Chapter 1.2.5

Homework

Now that you know how to create a Git repository and know the basics of HTML, let's get you started with creating the first part of your website!

Create Your Website Repositorry

For the first step, you will want to create the folder from which you will be editing and pushing your changes to GitHub.

First, navigate to a directory on your file system where you want to host the website project. Then, create a directory and some folders that we will use in the future. To do so, open the command line and paste the following (don't forget to use Git Bash if you're on Windows):

mkdir personal-website

cd personal-website

mkdir assets

cd assets

mkdir img

mkdir css

mkdir js

cd ..

Finally, initialize your repo:

git init

Create an HTML Document

Open Visual Studio Code and in the Top Left of your screen, select File > Open and select the folder you just created, personal-website.

Once you have successfully opened your folder, create a new file by selecting File > New File. Save it selecting File > Save and call it index.html. This will be the landing page that will come up first when people go to your website.

You can also type

touch index.htmlto create this file in the command line).

Copy the code below onto your index.html file. You may modify it as much as you'd like and we will be able to stylize it further in the future using CSS, JavaScript, and more advanced HTML tags!

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>My Portfolio Site</title>

<meta name="description" content="This is my own website!">

<meta name="author" content="YOURNAME">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/styles.css">

</head>

<body>

<script src="js/main.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Save the file by selecting File > Save.

Push Your Repo

Navigate back to Terminal (or Command Prompt on windows) and add all of the changes you have made to the repo so far by typing:

git add .

Check that there are no "Untracked" documents by typing

git status

If all of the documents are ready to be committed and you have finalized all of your changes, commit your project.

git commit -m "Initialized the repository."

Create a new repository on GitHub following the instructions in Chapter 1.2.3 and push your changes to the cloud. If you can see your files in the site for your repository online, you have done this succesfully! You are ready to start modifying your site.

Chapter 1.3 - Introduction to CSS and Advanced HTML.

In this chapter, you will learn about CSS, short for Cascading Style Sheets—a style sheet language designed to modify the appearance of HTML files. While HTML is used to structure how content appears on the website, CSS allows to style and organize the content so it looks visually appealing. CSS is the second building block of every website—once you know it, you will be capable of building any static website that doesn't require interactivity.

CSS is used to apply styles to specific elements in the HTML page that links to it (we will learn how to link HTML with CSS in the homework portion of this chapter). In order to write in CSS, you need to create a file that ends in .css. Once there, the syntax for each style is as follows:

selector {

property1: value1;

property2: value2;

...

}

We will discuss what selectors, properties, and values are in the following sections of this chapter.

Chapter 1.3.1 - Selectors

Selectors

As elements are added to a web page, they may be styled using CSS. A selector designates exactly which element or elements within our HTML to target and apply styles (such as color, size, and position) to. Selectors may include a combination of different qualifiers to select unique elements, all depending on how specific we wish to be. For example, we may want to select every paragraph on a page, or we may want to select only one specific paragraph on a page. Selectors generally target an attribute value, such as an id or class value, or target the type of element, such as <h1> or <p>. In CSS, selectors are followed by curly brackets, { }, which hold the styling that is applied to the selected element. In the following example, the selector 'p' is used to tell CSS to apply specific styles to the <p> elements.

To code and upkeep professional websites, it is important that you know how to properly classify different elements and apply styles: selectors play a crucial role in this.

Type Selectors

Type selectors target elements by their element type. For example, if we wish to target all division elements, <div>, we would use a type selector of div. The following two code snippets showcase the CSS selection as well as the elements that are selected in the HTML file.

CSS

div { ... }

HTML

<div>...</div>

<div>...</div>

Class Selectors

Class selectors allow us to select an element based on the element’s class attribute value. Class selectors are a little more specific than type selectors, as they select a particular group of elements rather than all elements of one type.

Class selectors allow us to apply the same styles to different elements at once by using the same class attribute value across multiple elements.

>In CSS, classes are denoted by a leading period, ., followed by class attribute value. In the next example, the class sector selects any elements containing the class attribute value of awesome including both division and paragraph elements.

CSS

.awesome {...}

HTML

<div class="awesome">...</div>

<p class="awesome">...</p>

ID Selectors

ID selectors are even more precise than class selectors, as they target only one unique element at a time. Just as class selectors use an element’s class attribute value as the selector, ID selectors use an element’s id attribute value as a selector.

id attribute values can only be used once per page. Reserve them for significant elements!

In CSS, ID selectors are denoted by a leading has sign, #, followed by the

idattribute value. In the following example, the ID selector will only select the element containing theidattribute value ofoval.

CSS

#oval {...}

HTML

<div id="oval">...</div>

In the previous chapter we talked about HTML attributes like id and class but omitted what they were used for. Now you know that they're mostly used to link CSS to them (among other reasons)!

Chapter 1.3.2 - The Cascade and Combining Selectors

The Cascade

Within CSS, all styles cascade from the top of a style sheet to the bottom, allowing different styles to be added or overwritten as the style sheet progresses.

For example, say we select all paragraph elements at the top of our style sheet and set their background color to orange and their font size to 24 pixels. Then towards the bottom of our style sheet, we select all paragraph elements again and set their background color to green, as seen here.

p {

background: orange;

font-size: 24px;

}

p {

background: green;

}

Because the paragraph selector that sets the background color to green comes after the paragraph selector that sets the background color to orange, it will take precedence in the cascade. All of the paragraphs will appear with a green background. The font size will remain 24 pixels because the second paragraph selector didn’t identify a new font size.

>The cascade also works with properties inside individual selectors. In the following example, the green property takes precedence over the orange.

p {

background: orange;

background: green;

}

If you want to make sure that some value won't be overwritten by another value, use !important key after the value (i.e., background: orange !important).

Selector Specificity Weight

Every selector in CSS has a specificity weight. A selector’s specificity weight, along with its placement in the cascade, identifies how its styles will be rendered.

You've learned about three types of selectors: type, class, and ID. A selector's specificity is calculated using three columns. They are outlined below as follows:

| selector | weight |

|---|---|

type | 0-0-1 |

class | 0-1-0 |

ID | 1-0-0 |

The first column counts ID selectors, the second column counts class selectors, and the third column counts type selectors. The ID selector has a higher specificity weight than the class selector, and the class selector has a higher specificity weight than the type selector. The higher the specificity weight of a selector, the more superiority the selector is given when a styling conflict occurs.

For example, if a paragraph element is selected using a type selector in one place and an ID selector in another, the ID selector will take precedence over the type selector regardless of where the ID selector appears in the cascade.

HTML

<p id="food">...</p>

CSS

#food {

background: green;

}

p {

background: orange;

}

In the above example we have a paragraph element with an ID attribute value of food. Within our CSS, that paragraph is being selected by two different kinds of selectors: one type selector and one ID selector. Although the type selector comes after the ID selector in the cascade, the ID selector takes precedence over the type selector because it has a higher specificity weight; consequently the paragraph will appear with a green background.

Combining Selectors

By combining selectors we can be more specific about which element or group of elements we’d like to select. For example, say we want to select all paragraph elements that reside within an element with a class attribute value of hotdog and set their background color to brown. However, if one of those paragraphs happens to have the class attribute value of mustard, we want to set its background color to yellow.

HTML

<div class="hotdog">

<p>...</p>

<p>...</p>

<p class="mustard">...</p>

</div>

CSS

.hotdog p {

background: brown;

}

.hotdog p.mustard {

background: yellow;

}

When selectors are combined they should be read from right to left. The selector farthest to the right, directly before the opening curly bracket, is known as the key selector. The key selector identifies exactly which element the styles will be applied to. Any selector to the left of the key selector will serve as a prequalifier.

Spaces Within Selectors

Since there isn’t a space between the paragraph type selector and the mustard class selector that means the selector will only select paragraph elements with the class of mustard. If the paragraph type selector was removed, and the mustard class selector had spaces on both sides of it, it would select any element with the class of mustard, not just paragraphs.

The best practice is to not prefix a class selector with a type selector. Generally we want to select any element with a given class, not just one type of element. And following this best practice, our new combined selector would be better as .hotdog .mustard.

Reading the combined selector from right to left, it is targeting paragraphs with a class attribute value of mustard that reside within an element with the class attribute value of hotdog.

Specificity Within Combined Selectors

When selectors are combined, so are the specificity weights of the individual selectors. These combined specificity weights can be calculated by counting each different type of selector within a combined selector

>Looking at our combined selectors from before, the first selector, .hotdog p, had both a class selector and a type selector. Knowing that the point value of a class selector is 0-1-0 and the point value of a type selector is 0-0-1, the total combined point value would be 0-1-1, found by adding up each kind of selector.

In general we want to always keep an eye on the specificity weights of our selectors. The higher our specificity weights rise, the more likely our cascade is to break.

Layering Styles with Multiple Classes

To keep the specificity weights of our selectors low we should consider being as modular as possible by sharing similar styles from element to element . We layer on different styles by using multiple classes.

Elements within HTML can have more than one class attribute value so long as each value is space separated. With that, we can place certain styles on all elements of one sort while placing other styles only on specific elements of that sort.

HTML

<a class="btn color-danger">....</a>

<a class="btn colorr-success">...</a>

CSS

.btn {

font-size: 16px;

}

.color-danger {

background: red;

}

.color-success {

background: green;

}

In the above example, we want our buttons to have a font size of 16 pixels; however, we want the background color of our buttons to vary depending on where the buttons are used. We create a few classes and layer them on an element as necessary.

Chapter 1.3.3 - Common CSS Property Values

Properties

Once an element is selected, a property determines the styles that will be applied to that element. Property names fall after a selector, within the curly brackets, {}, and immediately preceding a colon, :. There are numerous properties we can use, such as background, color, font-size, height, and width, and new properties are often added. In the following code, we are defining the color and font-size properties to be applied to all <p> elements.

p {

color: ...;

font-size: ...;

}

Values

We can determine the behavior of a property with a value. Values can be identified as the text between he color, :, and semicolon, ;. In the example below, we are selecting all <p> elements and setting the value of the color property to be orange and the value of the font-size property to be 16 pixels.

p {

color: orange;

font-size: 16px;

}

Note: it is common practice to indent the property and value pairs within the curly brackets (usually with 2 spaces, though 4 spaces are used in these examples).

Common CSS Property Values

There are a few ways to specify color and length property values. Those are outlined below respectively.

Colors

CSS defines color values on an sRGB (standard red, green, and blue) color space. We can form colors by combing red, green and blue color channels together at different levels. There are four ways to represent colors within CSS: keywords, hexadecimal notation, RGB and HSL values.

Keyword Colors

Keyword color values are names (such as red, green, or blue) that map to a given color. Most common colors have keyword names. You can find all of these keywords here.

.btn {

background: yellow;

}

.task {

background: red;

}

Here we apply the property value

yellowto the classbtnand the property valueredto the classtask.

Hexadecimal Colors

A hexadecimal color value begins with a # (pound or hash) followed by a six-character figure. The figures use the numbers 0 through 9 and the letters a through f. Since one hexadecimal digit can take 16 different values (0-9 and a-f), two of them combined can take 16*16=256 values. Each such pair defines red, green, and blue (RGB) color channels. For reasons we don't have to get into, RGB can show most of the visible colors, and it is used in web development and many other applications to define colors.

The color white, for example, is made by mixing each of the three primary colors at their full intensity, resulting in the Hex color code of #FFFFFF.

#FFFFFF

Black, the absence of any color on a screen display, is the complete opposite, with each color displayed at their lowest possible intensity and a Hex color code of #000000.

#000000

The color red can be made by using only the red channel and leaving blue and green channels at 0.

#FF0000

Understanding the basics of Hex color code notation we can create grayscale colors very easily, since they consist of equal intensities of each color:

#454545

#999999

You can find a full list of common hexademical color mappings here.

There are millions of hexadecimal colors, over 16.7 million to be exact. There are 16 options for every character in a hexadecimal color, 0 through 9 and A through F. With the characters grouped in pairs, there are 256 color options per pair (16 multiplied by 16, or 16 squared). And with three groups of 256 color options we have a total of over 16.7 million colors (256 multiplied by 256 multiplied by 256, or 256 cubed).

.btn {

background: #FFFF00;

}

.task {

background: #FF0000;

}

We can recreate the

yellowandredcolors from before by using their hexadecimal values.

RGB & RGBa Colors

RGB color values are stated using the rgb() function, which stands for red, green, and blue. The function accepts three comma-separated values, each of which is an integer from 0 to 255. A value of 0 would be pure black; a value of 255 would be pure white.

The first value within the rgb() function represents the red channel, the second value represents the green channel, and the third value represents the blue channel.

.btn {

background: rgb(255, 255, 0);

}

.task {

background: rgb(255, 0, 0);

}

We can, once again, recreate the

yellowandredcolors from before by using theirrgb()combination.

RGB color values may also include an alpha, or transparency, channel by using the rgba() function. The rgba() function requires a fourth value, which must be a number between 0 and 1, including decimals. A value of 0 creates a fully transparent color, meaning it would be invisible, and a value of 1 creates a fully opaque color. Any decimal value in between 0 and 1 would create a semi-transparent color.

.btn {

background: rgba(255, 255, 0, .25);

}

.task {

background: rgba(255, 0, 0, .1);

}

We can make our

yellowcolor 25% opaque by setting the final parameter to.25and, similarly, we can make ourredcolor 100% opaque by setting its last parameter to 1.

HSL & HSLa Colors

HSL color values are stated using the hsl() function, which stands for hue, saturation, and lightness. Within the parentheses, the function accepts three comma-separated values, much like rgb().

The first value, the hue, is a unitless number from 0 to 360. The numbers 0 through 360 represent the color wheel, and the value identifies the degree of a color on the color wheel.

The second and third values, the saturation and lightness, are percentage values from 0 to 100%. The saturation value identifies how saturated with color the hue is, with 0 being grayscale and 100% being fully saturated. The lightness identifies how dark or light the hue value is, with 0 being completely black and 100% being completely white.

.btn {

background: hsl(60, 100%, 50%);

}

.task {

background: hsl(0, 100%, 50%);

}

Using

hsl(), we can recreate our previous colors by setting the hue to60foryellowand0forred.

HSL color values, like RGBa, may also include an alpha, or transparency, channel with the use of the hsla() function. The behavior of the alpha channel is just like that of the rgba() function. A fourth value between 0 and 1, including decimals, must be added to the function to identify the degree of opacity.

.btn {

background: hsl(60, 100%, 50%, .25);

}

.task {

background: hsl(0, 100%, 50%, 1);

}

We can set the opacity of our

yellowcolor to 25% by setting the last parameter to.25and the opacity of ourredcolor to 100% by setting the last parameter to1.

Hexadecimal color values are the most widely used and supported amongst different browsers.

Lengths

We use two different types of lengths, absolute and relative, to set the size and shape of our elements in CSS.

Absolute Lengths

Absolute lengths represent physical measurements such as inches, centimeters, pixels and millimeters. The most popular absolute unit is the pixel, represented by the px unit notation.

The pixel is equal to 1/96th of an inch; thus there are 96 pixels in an inch. The exact measurement of a pixel, however, may vary slightly between high-density and low-density viewing devices.

p {

font-size: 14px;

}

We can use the pixel to set the font size of a

ptag to14px.

Pixels don't adapt too well from device to device but they are still a ubiquitous unit used in styling.

Relative Lengths

Relative lengths, by definition, are not fixed and thus they rely on the length of some other measurement.

Percentages

Percentage lengths are defined in relation to the length of another object.

.col {

width: 50%;

}

We can set the width of an element in the

colclass to be 50% of the parent element's width.

Em

The em unit is represented by the em unit notation, and its length is calculated based on an element's font size.

A single em unit is equivalent to an element’s font size. So, for example, if an element has a font size of 14 pixels and a width set to 5em, the width would equal 70 pixels (14 pixels multiplied by 5).

.banner {

font-size: 14px;

width: 5em;

}

When a font size is not explicitly stated, the em unit will be relative to the font size of the closest parent element with a stated font size. The em unit is often used for styling text, including font sizes, as well as spacing around text, including margins and paddings.

Rem

The rem unit is represented by the rem unit notation, and it is similar to em but it's length is calculated based on the website's font size. For example, while 1 em can be different from element to element (depending on its size and its parent elements' sizes), 1 rem will remain the same across the page. We will be mostly using rem since it is universal and allows for consistent design across different screens. It is also the unit used in Tailwind CSS, but more on that in Chapter 4.2.

Chapter 1.3.4 - Box Model

Box Model

In HTML, elements are classified either block- or inline-level. This has to do with how the elements are displayed.

| type of level | description |

|---|---|

| block |

|

| in-line |

|

Display

You can change how an element is displayed through the display property. Every element has a default display property but it can be overwritten to be block, inline, inline-block, and none.

p {

display:block;

}

A value of

blockwill make that element a block-level element.

p {

display: inline;

}

A value of

inlinewill make that element an inline-level element.

p {

display: inline-block;

}

With the

inline-blockvalue, the element behaves as a block-level element, accepting all box model properties; however, the element will be displayed in line with other elements, and it will not begin on a new line by default.

Paragraph one.

Paragraph two.

Paragraph three.

Three paragraph elements displayed

inline, sitting right next to the other in a horizontal line.

div {

display: none;

}

An element displayed as

nonewill not appear on the page.

What is the Box Model?

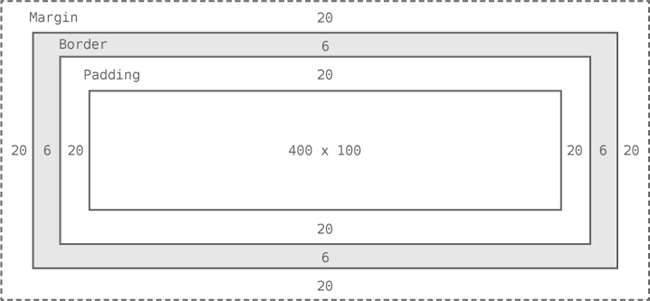

Every element on a page is a essentially rectangular with a width, height, padding, borders, and margins.

You can see in the above example that all elements are rectangular, regardless of their shape.

Working with the Box Model

Every element has a set of properties which determine its size.

| property | description |

|---|---|

display | could determine width and height |

width and height | explicit length of width and height values |

padding and border | expand the dimensions of the box outward from the element's width and height |

margin | any margins specified follow the border |

Each part of the box model corresponds to a CSS property.

div {

border: 6px solid #9495599;

height: 100px;

margin: 20px;

padding: 20px;

width: 400px;

}

We can calculate the width of the hypothetical element above with the following formula:

margin-right + border-right + padding-right + width + padding-left + border-left + margin_left. The total height of an element can be calculated using the following formula:margin-top + border-top + padding-top + height + padding-bottom + border-bottom + margin-bottom.

- Width:

492px = 20px + 6px + 20px + 400px + 20px + 6px + 20px - Height:

192px = 20px + 6px + 20px + 100px + 20px + 6px + 20px

The box model for the previous example, visualized.

Each property has a different way of interacting with the content surrounding it.

| property | description |

|---|---|

width |

|

height |

|

margin |

|

padding |

|

Shorthand and Longhand

The margin and padding properties come in both longhand and shorthand from. When using the shorthand margin property to set the same value for all four sides of an element, we specify one value:

div {

margin: 20px;

}

To set one value for the top and bottom and another for the left and right sides, specify two values: top and bottom first, then left and right.

div {

margin: 10px 20px;

}

You can specify unique values for all four sides by specifying them in order of top, right, bottom, and left, moving clockwise.

div {

margin: 10px 20px 0 15px;

}

Any of these options are considered shorthand. Longhand involves explicitly stating the property and side you would like to modify.

div {

margin-top: 10px;

padding-left: 6px;

}

In the above example, we set our

margin-topproperty value to be10pxand ourpadding-leftproperty to be6px;

It is best to use longhand notation when we wish to identify only one margin or padding value. This keeps our code explicit and helps us avoid any confusion.

Border

The border property requires three values: width, style and color. Shorthand values for the border property are stated in that order--width, style, color. In longhand, we break these three values into the border-width, border-style and border-color properties. They are useful for overwriting a single property value.

The most common border styles are solid, double, dashed, dotted, and none.

Just like the margin and padding properties, border has highly specific longhand sub properties. These highly specific longhand border properties include a series of hyphen-separated words starting with the border base, followed by the selected side—top, right, bottom, or left—and then width, style, or color, depending on the desired property.

div {

border-bottom: 6px solid #949599;

}

In the above example, we created a border solely on the bottom side of the

divelement.

div {

border-bottom-width: 12px;

}

Styles for individual border sides may be controlled at a fine level. In the above code, we change the width of the

bottomborderto12px.

To round the corners of border, we use the border-radius property. This property accepts length units, including percentages and pixels, that identify the radius by which the corners of an element to be rounded.

Similarly to the margin and padding shorthand notation, we can specify the radius of all corners equally by giving one value, the radius of top/bottom and right/left with two, and the radius of individual corners with four values, going in a clockwise direction.

div {

border-radius: 5px 0 15px 20px;

}

In the above example, we set the radius of the

top-left,top-right,bottom-right,bottom-leftcorner to5px,0,15px, and20pxrespectively.

You may even set the individual border-radius of a corner usingborder- followed by a specific corner and the word radius.

div {

border-top-right-radius: 5px;

}

In the above example, we change the

radiusof thetop-rightcorner to be5px.

Box Sizing

We have discussed the the additive nature of the box model where width, padding and border contribute to the overall width of an element. CSS3 introuced the box-sizing property which allows us to change how the box model works and in turn how an element's size is calculated. The three primary values it accepts are content-box, padding-box, and border-box.

Content Box

The content-box value is the default value.

Padding Box

The padding-box value alters the box model by including the padding property values within the width and height of an element. When using the padding-box value, if an element has a width of 400 pixels and a padding of 20 pixels around every side, the actual width will remain 400 pixels. As any padding values increase, the content size within an element shrinks proportionately.

If we add a border or margin, those values will be added to the width or height properties to calculate the full box size. For example, if we add a border of 10 pixels and a padding of 20 pixels around every side of the element with a width of 400 pixels, the actual full width will become 420 pixels.

div {

box-sizing: padding-box;

}

Border Box

The border-box value alters the box model so that any border or padding property values are included within the width and height of an element. When using the border-box value, if an element has a width of 400 pixels, a padding of 20 pixels around every side, and a border of 10 pixels around every side, the actual width will remain 400 pixels.

If we a margin, those values need to be added to calculate the full box size.

>No matter which box-sizing property value is used, any margin values will need to be added to calculate the full size of the element.

div {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

Generally speaking, the best box-sizing value to use is border-box. The border-box value makes our math much, much easier. If we want an element to be 400 pixels wide, it is, and it will remain 400 pixels wide no matter what padding or border values we add to it.

box-sizingis not supported in every browser so if you encounter displaying issues, consider this a potential source of error.

Chapter 1.3.5 - Advanced HTML Formatting

Advanced HTML Formatting

In Chapter 1.2.4, you learned about the HTML document and its tag-based syntax. In this chapter, you will explore more advanced HTML tags that will help you format your code for ease of readability and illustration.

Tags

There are a few key tags that are incredibly useful to know, let's walk you through them.

Links

A link or hyperlink is a connection from one web resource to another. Links allow users to move seamlessly from one page to another, on any server anywhere in the world.A link or hyperlink is a connection from one web resource to another. Links allow users to move seamlessly from one page to another, on any server anywhere in the world.

A link has two ends, called anchors. The link starts at the source anchor and points to the destination anchor, which may be any web resource, for example, an image, an audio or video clip, a PDF file, an HTML document or an element within the document itself, and so on.

We can specify a link in HTML by using the <a> tag. This could be a word, group of words, or even an image.

<a href="url">Link text</a>

In the example above, we generated this Link text.

The href attrilbute specifes the target of the link and its value can be an absolute or relative URL.

| URL | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Relative | images/smiley.png | includes every part of the URL format, such as protocol, host name, and path of the document. |

| Absolute | https://oval-webdev.netlify.app/syllabus.html | are page-relative paths, never include the http:// or https:// prefix. |

Set Targets for Links

You can add a target attribut to your <a> tags to specify to the browser how it should open a linked document.

target | Description |

|---|---|

_blank | Opens the linked document in a new window or tab. |

_parent | Opens the linked document in the parent window. |

_self | Opens the linked document in the same window/tab as the source. This is the default behaviour and can be omitted. |

_top | Opens the linked document in the full browser window. |

<a href="https://www.google.com" target="_blank">Google.</a>

The above example generates this link: Google.

Create Bookmark Anchors

You can create bookmark anchors to allow users to jump to specific sections of a web page. These are useful for very long web pages.

This is a two step process:

- Add the

idattribute on the element where you want to jump. - Use the

idattribute value preceded by the has sign (#) as the value of thehrefattribute of the<a>tag.

<a href="#sectionX">Jump to Section X</a>

<h2 id="sectionX">Section X</h2>

The above example creates this link: Jump to Section X

...which jumps to here:

Section X

Text Formatting

HTML provides you with several tags that can be used to make text on your web site appear different from normal text.

<p>This is <b>bold text</b>.</p>

<p>This is <strong>strongly important text</strong>.</p>

<p>This is <i>italic text</i>.</p>

<p>This is <em>emphasized text</em>.</p>

<p>This is <mark>highlighted text</mark>.</p>

<p>This is <code>computer code</code>.</p>

<p>This is <small>smaller text</small>.</p>

<p>This is <sub>subscript</sub> and <sup>superscript</sup> text.</p>

<p>This is <del>deleted text</del>.</p>

<p>This is <ins>inserted text</ins>.</p>

In the above example, you can see the most commonly used formatting tags. This is how they would appear:

This is bold text.

This is strongly important text.

This is italic text.

This is emphasized text.

This is highlighted text.

This is computer code.

This is smaller text.

This is subscript and superscript text.

This is deleted text.

This is inserted text.

Quotations

To format quotation blocks from other sources, you should use the blockquote tag.

<blockquote>

<p>Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.</p>

<cite>— Albert Einstein</cite>

</blockquote>

The above example showcases the

blockquotetag in action. Thecitetag is used to describe a reference to a creative work. This is how it appears:

Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.

— Albert Einstein

For short inline quoatations, you use the HTML <q> tag.

<p>According to the World Health Organization (WHO): <q>Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.</q></p>

According to the World Health Organization (WHO):

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.

To display an address, use the <address> tag.

<address>

Mozilla Foundation<br>

331 E. Evelyn Avenue<br>

Mountain View, CA 94041, USA

</address>

The above example would appear as follows:

Mozilla Foundation

331 E. Evelyn Avenue

Mountain View, CA 94041, USA

Images

You can add images to your site by using the <img> tag. This tag contains attributes only.

<img src="https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ducks-walk-on-glass-roof-video.jpg" alt="duckss">

The above image displays ducks:

The

srcattribute tells the browser where to find the image. Thealttag provides an alternative text for the image.

You can set the width of an image using the width and height attributes.

<img src="https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ducks-walk-on-glass-roof-video.jpg" alt="ducks" width="200px" height="100px">

The above code produces the following image:

Below is a list of all of the currently available and useful HTML5 tags. You may try them out by navigating to this website, copy/pasting the html snippet at the bottom of this page, and running the project. You may also modify your index.html file in your project repossitory.

| Tag | Description | End Tag? |

|---|---|---|

<a> | Defines a hyperlink. | |

<abbr> | Defines an abbreviated form of a longer word or phrase. | |

<address> | Specifies the author's contact information. | |

<area> | Defines a specific area within an image map. | |

<article> | Defines an article. | |

<aside> | Defines some content loosely related to the page content. | |

<audio> | Embeds a sound, or an audio stream in an HTML document. | |

<b> | Displays text in a bold style. | |

<base> | Defines the base URL for all relative URLs in a document. | |

<bdi> | Represents text that is isolated from its surrounding for the purposes of bidirectional text formatting. | |

<bdo> | Overrides the current text direction. | |

<blockquote> | Represents a section that is quoted from another source. | |

<body> | Defines the document's body. | |

<br> | Produces a single line break. | |

<button> | Creates a clickable button. | |

<canvas> | Defines a region in the document, which can be used to draw graphics on the fly via scripting (usually JavaScript). | |

<caption> | Defines the caption or title of the table. | |

<cite> | Indicatess a citation or reference to another source. | |

<code> | Specifies text as computer code. | |

<col> | Defines attribute values for one or more columns in a table. | |

<colgroup> | Specifies attributes for multiple columns in a table. | |

<data> | Links a piece of content with a machine-readable translation. | |

<datalist> | Represents a set of pre-defined options for an <input> element. | |

<dd> | Specifies a description, or value for the term (<dt>) in a description list (<dl>). | |

<del> | Represents text that has been deleted from the document. | |

<details> | Represents a widget from which the user can obtain additional information or controls on-demand. | |

<dfn> | Specifies a definition. | |

<dialog> | Defines a dialog box or sub window. | |

<div> | Specifies a division or a section in a document. | |

<dl> | Defines a description list. | |

<dt> | Defines a term (an item) in a description list. | |

<em> | Defines emphasized text. | |

<embed> | Embeds external application, typically multimedia content like audio or video into an HTML document. | |

<fieldset> | Specifies a set of related form fields. | |

<figcaption> | Defines a caption or legend for a figure. | |

<figure> | Represents a figure illustrated as part of the document. | |

<footer> | Represents the footer of a document or a section. | |

<form> | Defines an HTML form for user input. | |

<head> | Defines the head portion of the document that contains information about the document such as title. | |

<header> | Represents the header of a document or a section. | |

<hgroup> | Defines a group of headings. | |

<h1 to <h6> | Defines HTML headings. | |

<hr> | Produce a horizontal line. | |

<html> | Defines the root of an HTML document. | |

<i> | Displays text in an italic style. | |

<iframe> | Displays a URL in an inline frame. | |

<img> | Represents an image. | |

<input> | Defines an input control | |

<ins> | Defines a block of text that has been inserted into a document. | |

<kbd> | Specifies text as keyboard input. | |

<keygen> | Represents a control for generating a public-private key pair. | |

<label> | Defines a label for an <input> control. | |

<legend> | Defines a caption for a <fieldset> element. | |

<li> | Defines a list item. | |

<link> | Defines the relationship between the current document and an external resource. | |

<main> | Represents the main or dominant content of the document. | |

<map> | Defines a client-side image-map. | |

<mark> | Represents text highlighted for reference purposes. | |

<menu> | Represents a list of commands. | |

<menuitem> | Defines a list (or menuitem) of commands that a user can perform. | |

<meta> | Provides structured metadata about the document content. | |

<meter> | Represents a scalar measurement within a known range. | |

<nav> | Defines a section of navigation links. | |

<noscript> | Defines alternative content to display when the browser doesn't support scripting. | |

<object> | Defines an embedded object. | |

<ol> | Defines an ordered list. | |

<optgroup> | Defines a group of related options in a selection list. | |

<option> | Defines an option in a selection list. | |

<output> | Represents the result of a calculation. | |

<p> | Defines a paragraph. | |

<param> | Defines a parameter for an object or applet element. | |

<picture> | Defines a container for multiple image sources. | |

<pre> | Defines a block of preformatted text. | |

<progress> | Represents the completion progress of a task. | |

<q> | Defines a short inline quotation. | |

<rp> | Provides fall-back parenthesis for browsers that don't support ruby annotations. | |

<rt> | Defines the pronounciation of character presented in a ruby annotation. | |

<ruby> | Represents a ruby annotation. | |

<s> | Represents contents that are no longer accurate or no longer relevant. | |

<samp> | Specifies text as sample output from a computer program. | |

<script> | Places script in the document for a client-side processing. | |

<section> | Defines a section of a document, such as header, footer, etc. | |

<select> | Defines a selection list within a form. | |

<small> | Displays text in a smaller size. | |